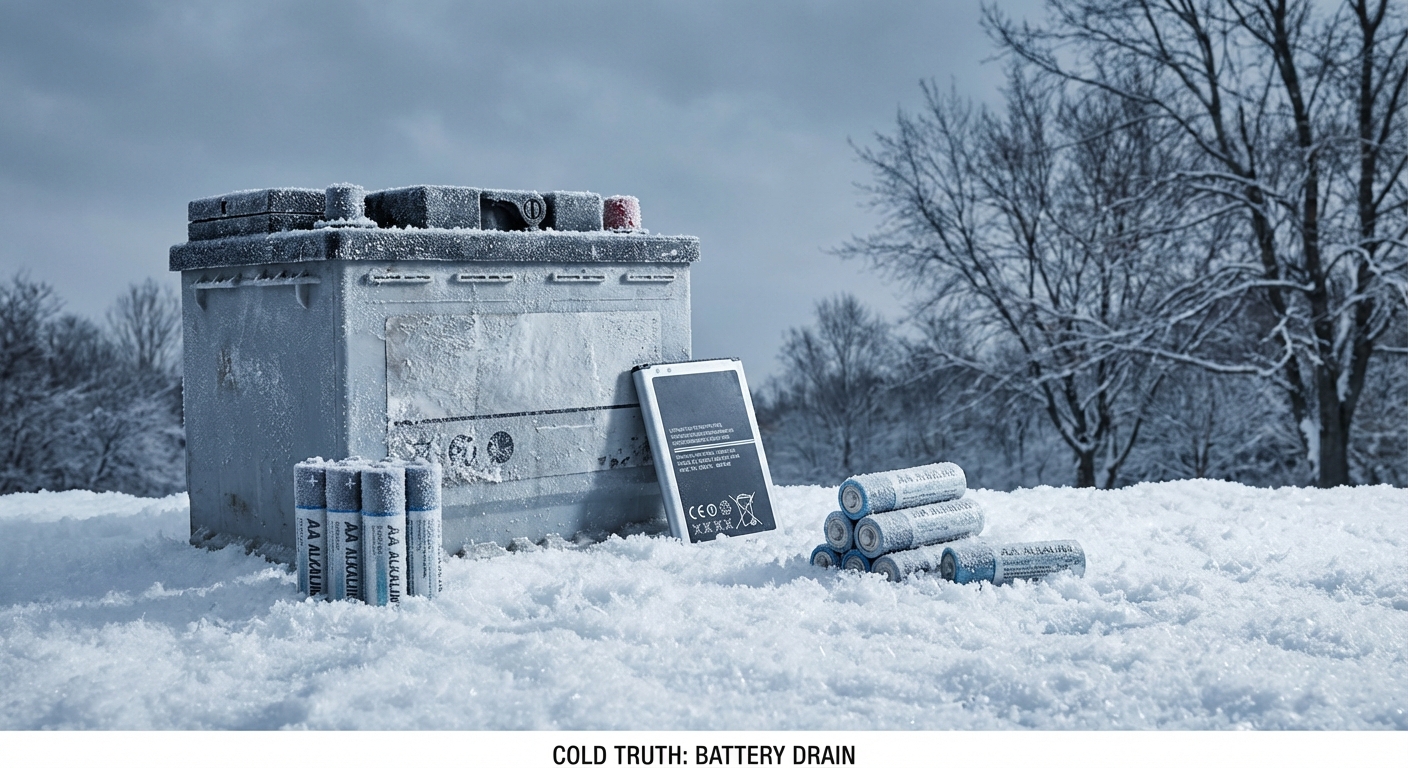

Why do batteries drain faster in cold weather? All batteries produce electricity through chemical reactions, and cold temperatures slow those reactions down. When the chemistry happens more slowly, the battery can’t deliver as much power at any given moment. Your phone, car, or flashlight demands the same power regardless of temperature, but a cold battery struggles to supply it, appearing to drain much faster than normal.

This isn’t a flaw in battery design but fundamental chemistry. The effect applies to every type of battery, from the lithium-ion cells in your devices to the lead-acid battery in your car. Understanding why it happens helps you prepare and protect your batteries when temperatures drop.

The Chemistry Behind Battery Performance

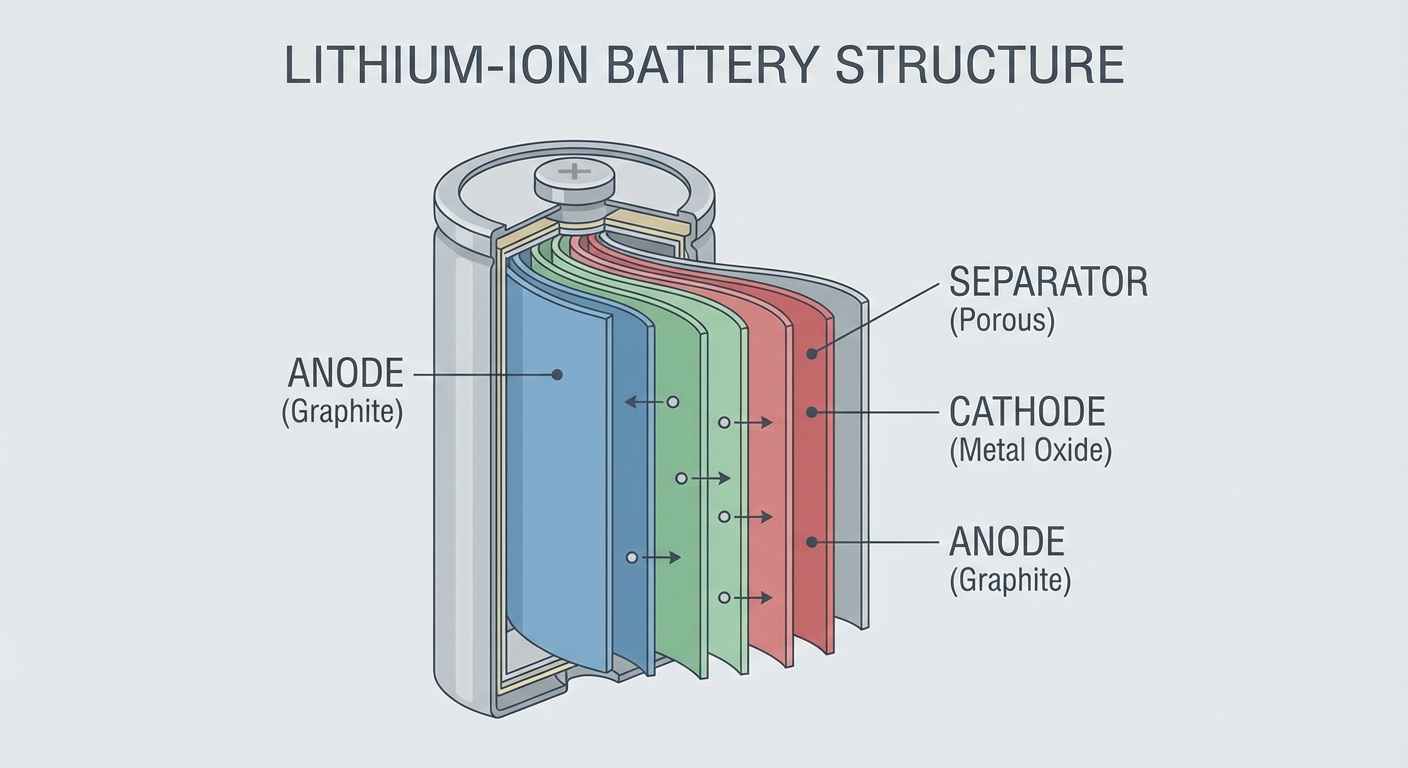

Batteries store energy in chemical form and release it as electricity. In a lithium-ion battery, lithium ions move between two electrodes through a liquid electrolyte. In a car’s lead-acid battery, sulfuric acid reacts with lead plates. In alkaline household batteries, zinc reacts with manganese dioxide.

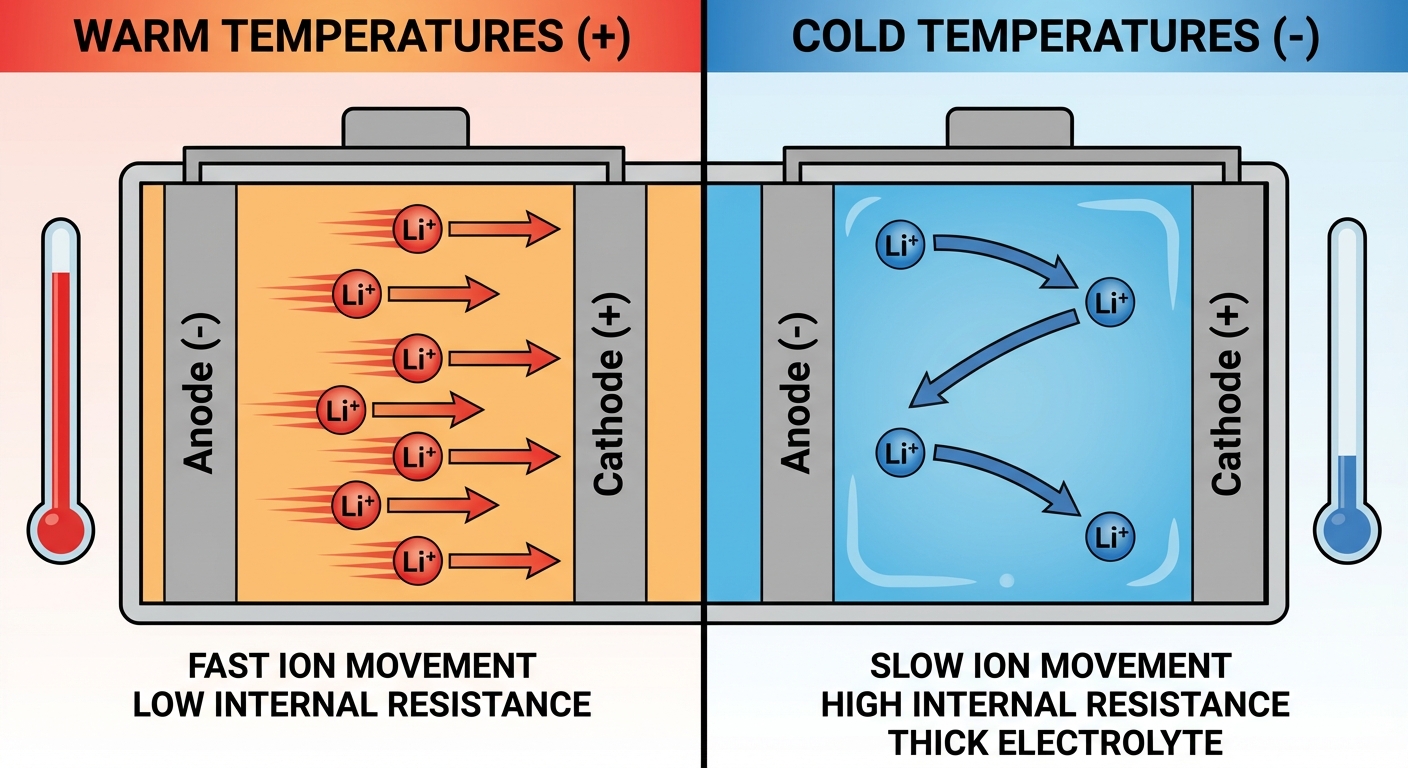

All chemical reactions are temperature-sensitive. Molecules move faster at higher temperatures, increasing the chance of collisions that drive reactions forward. Cold temperatures have the opposite effect: molecules move sluggishly, and reactions proceed more slowly.

In batteries, this means ions move through the electrolyte more slowly in cold conditions. The electrolyte itself often becomes more viscous, creating additional resistance. The result is reduced current flow: the battery can’t release stored energy as quickly as it could when warm.

Different Batteries, Similar Problems

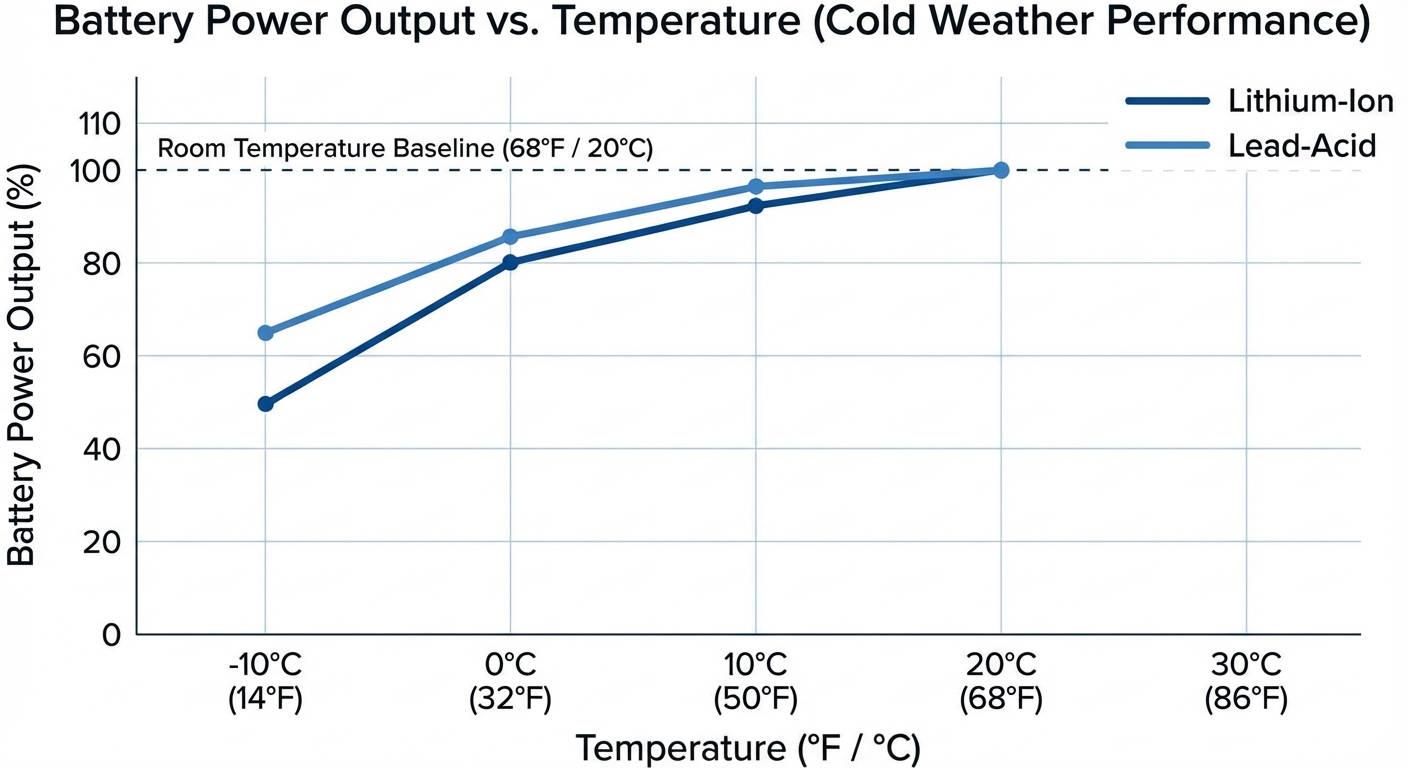

While all batteries suffer in cold, the specific effects vary by type.

Lithium-ion batteries (phones, laptops, electric vehicles) experience dramatic capacity loss in cold. At 32°F (0°C), a lithium-ion battery might deliver only 80% of its room-temperature capacity. At -4°F (-20°C), capacity can drop to 50% or less. The electrolyte thickens, impeding ion movement, and internal resistance increases.

Lead-acid batteries (cars, motorcycles) face compounded challenges. Cold reduces available power just when your engine is hardest to start. Motor oil thickens in cold weather, requiring more power to crank the engine. Meanwhile, the battery provides less. This double impact is why car batteries famously fail on the coldest mornings.

Alkaline batteries (household AA, AAA, etc.) also suffer reduced performance in cold, though less dramatically than lithium-ion. Their electrolyte doesn’t thicken as much, but the underlying chemical reaction still slows.

The Power Versus Capacity Distinction

Cold weather affects battery power (how quickly energy can be delivered) more than capacity (total energy stored). This distinction matters for understanding what’s really happening.

A cold battery hasn’t lost its charge. The energy is still there, but the battery can’t deliver it fast enough to meet device demands. When a phone shuts down at 30% in cold weather, then shows 40% after warming up, no charge was lost or gained. The battery simply couldn’t access its stored energy when cold.

Think of it like honey: refrigerated honey doesn’t disappear, but it pours extremely slowly. The honey is all there, just temporarily inaccessible at useful speed. Warming restores normal flow.

This is why temporary cold exposure doesn’t permanently damage most batteries. Once warmed, full capacity returns. The exception is extreme cold combined with charging, which can cause permanent damage to lithium-ion batteries.

Electric Vehicles and Cold Weather Range

Electric vehicle range reduction in cold weather illustrates battery chemistry effects at scale. EV owners routinely report 20-40% range loss in winter, a significant practical impact.

Part of this reduction comes from battery chemistry limitations. Cold cells deliver less power and accept regenerative braking energy less efficiently. But EVs face additional cold-weather burdens: cabin heating requires substantial electricity (unlike gas cars, which use waste engine heat), battery heating systems protect the pack but consume energy, and rolling resistance increases slightly on cold roads.

Many EVs pre-condition their batteries while plugged in, warming them to optimal temperature before departure. This preserves range and battery health but requires planning and access to charging.

How to Protect Batteries in Cold Weather

For phones and portable devices, keep them close to your body in cold weather. An inside pocket, warmed by body heat, maintains battery temperature better than an outside jacket pocket. Minimize use in extreme cold.

For car batteries, keep them fully charged going into winter. A fully charged battery resists freezing better than a partially discharged one and provides more starting power. If your battery is more than three years old, have it tested before winter. Park in a garage if possible.

For any device, avoid charging cold batteries. Lithium-ion batteries suffer permanent damage when charged below freezing, as lithium can plate onto the anode rather than intercalate properly. Let devices warm up before plugging them in.

Don’t use artificial heat sources like hair dryers or heaters to warm batteries. Rapid temperature changes can cause internal stress or condensation. Gradual warming at room temperature is safe.

Summary

Batteries drain faster in cold weather because low temperatures slow the chemical reactions that generate electricity. The battery can’t deliver power as quickly as devices demand, causing them to die earlier or shut down unexpectedly.

This affects all battery types: lithium-ion (phones, EVs), lead-acid (cars), and alkaline (household). The energy isn’t lost; it’s temporarily inaccessible. Once warmed, batteries return to normal capacity. Protect devices by keeping them warm, avoid charging cold batteries, and ensure car batteries are fully charged before winter cold arrives.