That battery health percentage dropping from 100% to 85% isn’t a conspiracy to make you buy a new phone. It’s chemistry. Lithium-ion batteries physically degrade with every charge cycle, and this process is unavoidable. Understanding why it happens helps you slow it down, but there’s no method to prevent it entirely.

The Short Answer: Lithium-ion batteries degrade because charging and discharging causes physical and chemical changes to the battery materials. Lithium ions moving between electrodes gradually damage the electrode surfaces, creating deposits that trap lithium and reduce the battery’s capacity to hold charge. Heat accelerates this damage significantly. Most phone batteries retain about 80% of their original capacity after 500 complete charge cycles, which typically translates to two to three years of normal use.

That’s the summary, but the actual mechanisms are fascinating if you want to understand what’s happening inside that little rectangle of stored energy in your pocket.

The Chemistry Behind the Decline

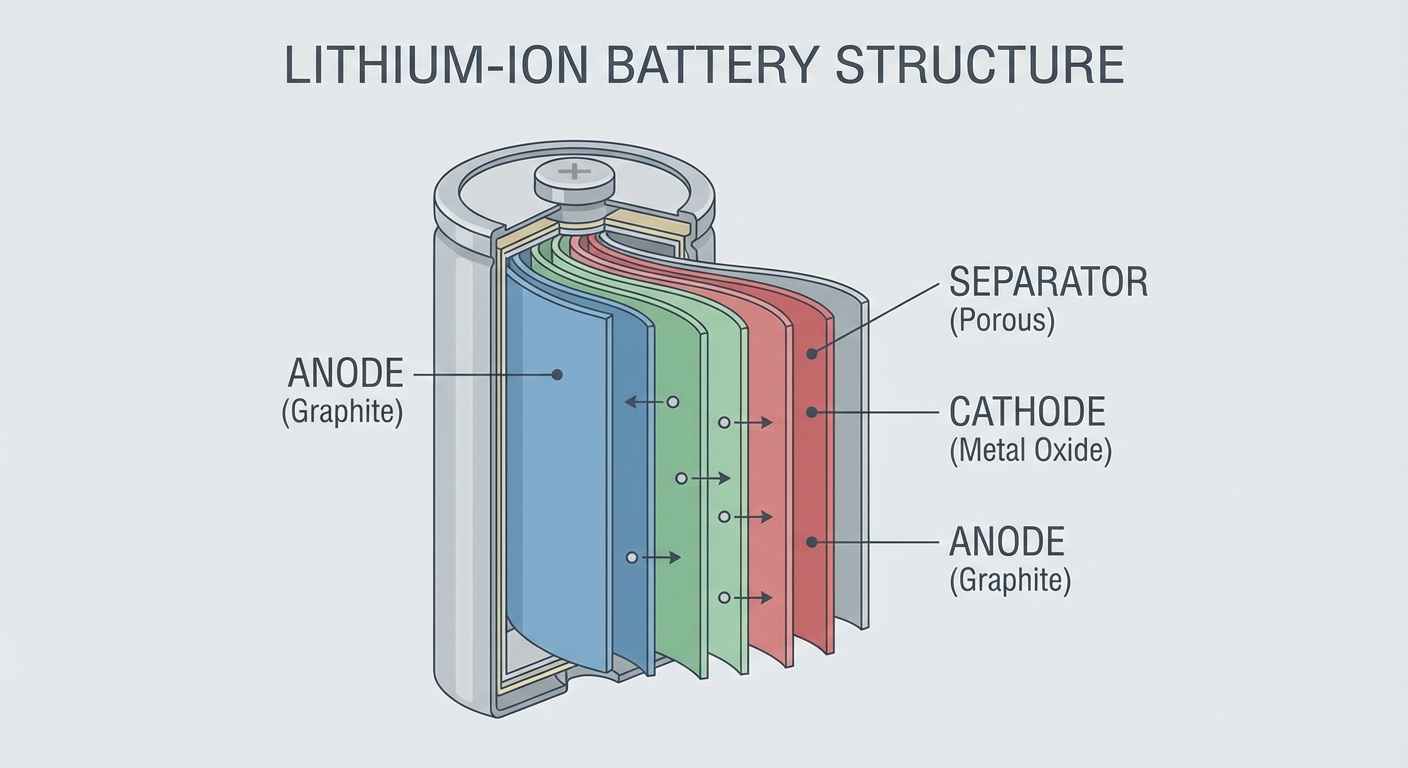

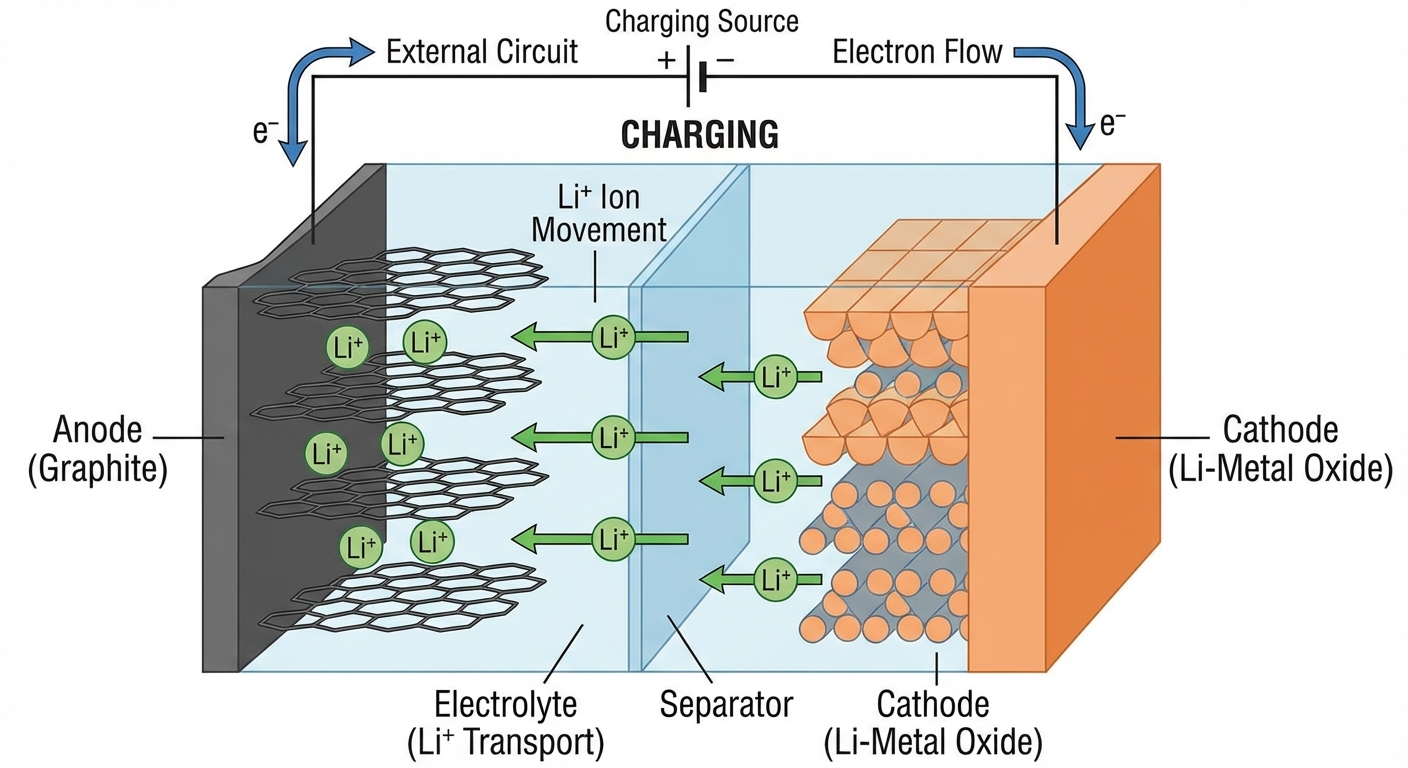

Lithium-ion batteries work by shuttling lithium ions between two electrodes: a graphite anode (negative) and a lithium metal oxide cathode (positive). When you charge your phone, lithium ions travel from the cathode through an electrolyte solution and embed themselves in the graphite anode. When you use your phone, those ions travel back to the cathode, releasing energy that powers your device.

This back-and-forth movement seems elegant and reversible, but it isn’t entirely. Each cycle causes tiny amounts of damage. The graphite anode’s structure subtly changes as lithium ions push in and out, creating micro-fractures. The cathode’s crystalline structure also degrades, with some lithium ions becoming permanently trapped rather than continuing to cycle.

The most significant damage occurs at the boundary between the anode and the electrolyte, where a layer called the Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) forms during the battery’s first few charges. This layer is actually necessary for the battery to function; it protects the anode from direct contact with the electrolyte. However, the SEI layer continues to grow slowly throughout the battery’s life, consuming both electrolyte and active lithium. Every bit of lithium locked up in the SEI is lithium that can no longer carry charge between electrodes.

Why Heat Is Your Battery’s Worst Enemy

Temperature affects battery degradation more than almost any other factor. High temperatures accelerate every degradation mechanism: SEI growth speeds up, cathode materials break down faster, and unwanted chemical reactions between the electrolyte and electrodes increase dramatically. A battery stored at 40°C (104°F) degrades roughly twice as fast as one stored at 25°C (77°F).

This is why charging your phone while using processor-intensive apps feels concerning, and why that concern is justified. The phone generates heat from the processor while simultaneously generating heat from charging. Combined temperatures can reach levels that measurably accelerate battery wear. Wireless charging generates more heat than wired charging because of energy losses in the inductive transfer, making it slightly harder on batteries over time.

Cold temperatures present a different problem. While cold doesn’t permanently damage batteries the way heat does, extremely low temperatures temporarily reduce battery capacity and can cause lithium plating if you try to charge in very cold conditions. Lithium plating occurs when lithium ions can’t embed properly in the cold anode and instead deposit as metallic lithium on the surface, which can cause permanent capacity loss.

Charge Cycles and the 80% Rule

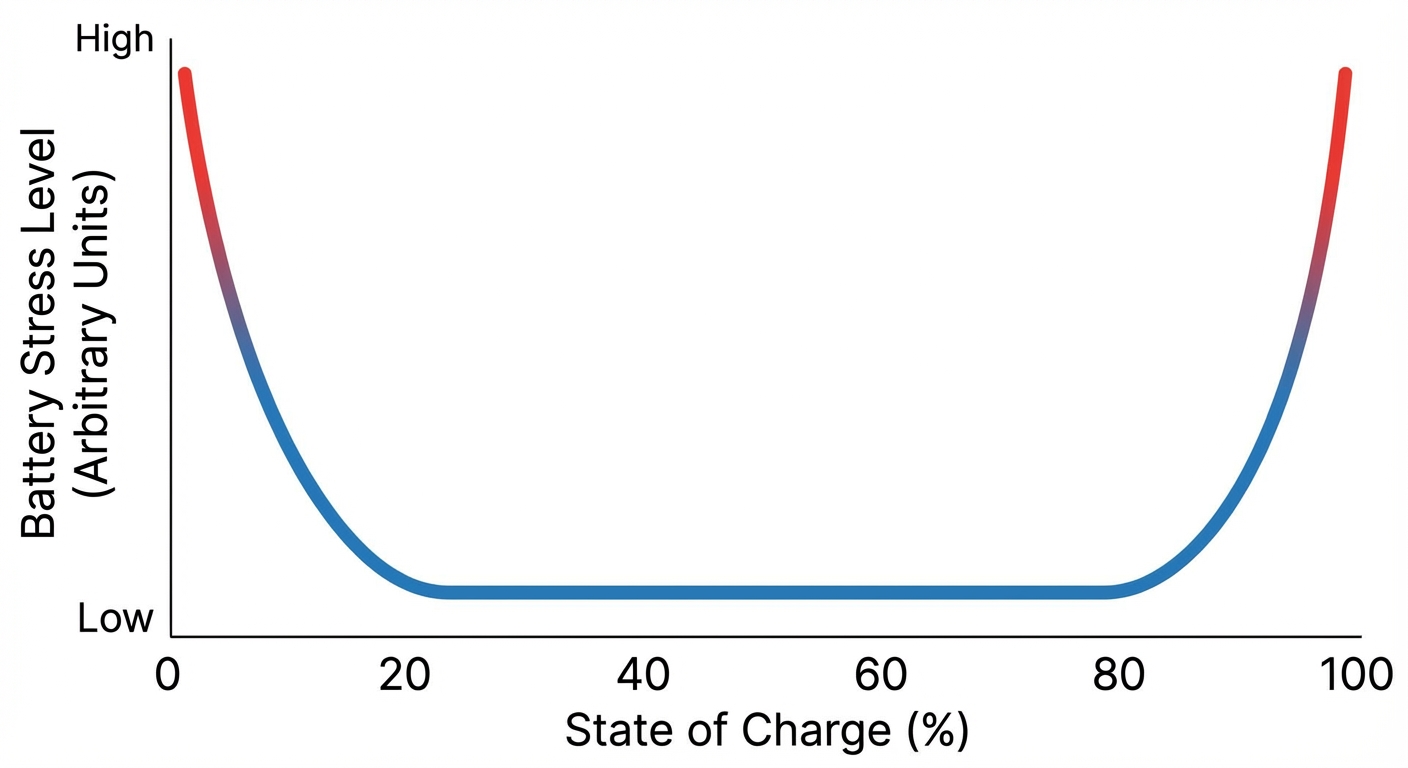

You’ve probably heard that you should keep your battery between 20% and 80% rather than charging to 100%. This advice has a real basis in battery chemistry, though the effect is less dramatic than some people believe.

At high charge states (above 80%), the cathode material is under significant physical stress because most of its lithium has been removed. At low charge states (below 20%), the anode is similarly stressed. Keeping batteries in these stressed states accelerates degradation. This is why most electric vehicles default to charging only to 80% for daily use, reserving the full 100% for long trips where maximum range is needed.

For phones, the practical impact is more modest. Modern phones include battery management systems that prevent true 0% and 100% states; what your phone shows as 0% or 100% is actually somewhat buffered. Still, avoiding extended time at full charge does provide some benefit. If you charge overnight, consider using scheduled charging features that delay reaching full charge until shortly before you wake up.

The “cycle” concept also deserves clarification. A charge cycle isn’t completed every time you plug in your phone. One cycle equals 100% of battery capacity discharged, regardless of how many separate sessions that takes. Charging from 60% to 80% four times equals about one cycle. This means topping off frequently doesn’t inherently cause more wear than deep discharges.

Fast Charging: Convenience vs. Longevity

Fast charging technologies deliver substantially more power to your battery than standard charging, and physics dictates that this generates more heat. More heat means faster degradation, all else being equal. However, phone manufacturers have invested heavily in managing this tradeoff, implementing sophisticated charging algorithms that reduce power delivery as the battery approaches full and as temperatures rise.

The real-world impact depends on implementation. Modern fast charging systems from major manufacturers are designed to minimize long-term damage while delivering speed benefits. Cheap third-party chargers that claim fast charging capabilities without proper temperature management present greater risks. Using the charger that came with your phone, or a certified replacement, provides the safest fast charging experience.

If battery longevity is a priority, using standard charging overnight and reserving fast charging for when you genuinely need quick top-ups represents a reasonable compromise. The speed difference only matters when you’re in a hurry; overnight charging has plenty of time regardless of wattage.

What Actually Extends Battery Lifespan

Given the chemistry involved, the most effective strategies for preserving battery health are straightforward: minimize heat exposure, avoid extended periods at very high or very low charge states, and use reputable charging equipment. Specific practices that help include removing phone cases during intensive charging sessions, avoiding charging in direct sunlight or hot cars, enabling optimized charging features that learn your schedule, and not leaving phones plugged in for days at a time.

Some degradation remains unavoidable. Even a phone stored turned off at perfect temperature will lose capacity over time because some degradation reactions occur regardless of cycling. The SEI layer continues growing, albeit slowly, and cathode materials degrade through exposure to the electrolyte. A battery that’s never used might retain 90% capacity after two years rather than 80%, but it will still degrade.

Summary

Phone batteries degrade because the chemistry of lithium-ion technology involves unavoidable physical and chemical changes with every charge cycle. Heat dramatically accelerates this degradation, making temperature management the most important factor in preserving battery health. Keeping charge states moderate (avoiding extended time at very high or very low percentages) provides additional benefit, though modern battery management systems already buffer the extremes. Fast charging is fine when you need it, but standard charging is gentler on long-term battery health.

Your battery will still degrade. The goal is reaching the typical two-to-three-year replacement point with closer to 85% capacity rather than 75%, which translates to meaningful extra life before battery performance becomes frustrating.

Sources: Battery University, Department of Energy Battery Research, Nature Energy, IEEE Spectrum Battery Coverage