What is a sinking fund? A sinking fund is money you set aside regularly for a specific future expense. Instead of scrambling when car insurance comes due or holiday shopping arrives, you save a small amount each month so the money is ready when you need it. The expense becomes planned rather than surprising, and you avoid using credit cards or raiding your emergency fund for costs you could have predicted.

The concept is simple: identify expenses that don’t occur monthly but do occur predictably, then divide the total cost by the months until payment is due. Your annual $1,200 car insurance premium becomes $100 per month in a dedicated sinking fund. When the bill arrives, the money is waiting. No stress, no debt, no dipping into savings meant for actual emergencies.

How Sinking Funds Differ From Emergency Funds

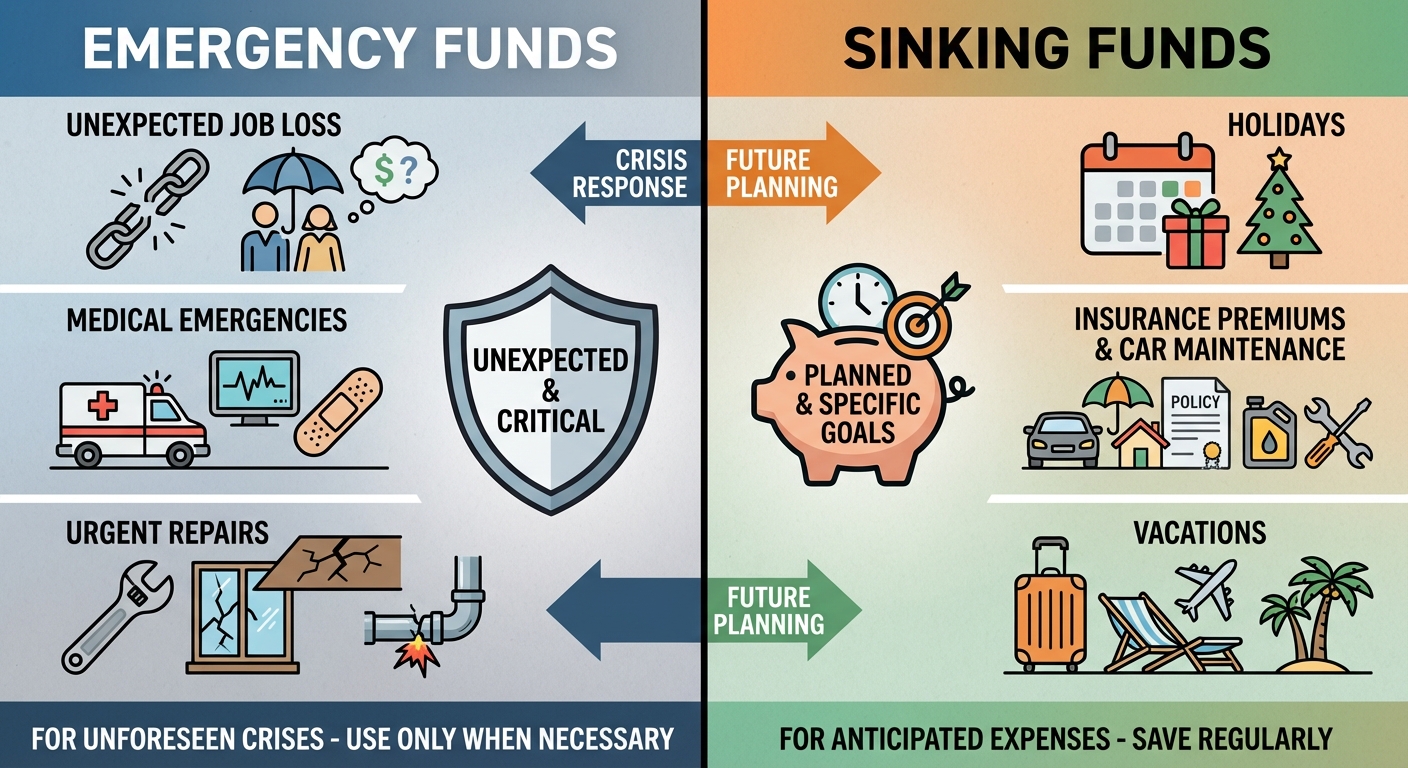

Many people confuse sinking funds with emergency savings, but they serve completely different purposes. Understanding the distinction helps you use both effectively.

Emergency funds cover unexpected, unpredictable expenses: job loss, medical emergencies, major home repairs you couldn’t anticipate. Financial advisors typically recommend three to six months of living expenses in an emergency fund. This money sits untouched until a genuine emergency occurs.

Sinking funds cover expected, predictable expenses that just don’t happen monthly. You know Christmas comes every December. You know your car will eventually need new tires. You know your annual subscriptions will renew. None of these are emergencies; they’re certainties you can prepare for.

The problem with using emergency funds for predictable expenses is depletion. If you tap your emergency fund for holiday gifts, new tires, and insurance premiums, it won’t be there when an actual emergency hits. Sinking funds protect your emergency fund by handling everything that isn’t truly unexpected.

According to the Federal Reserve, 37% of Americans would struggle to cover a $400 emergency expense without borrowing or selling something. Sinking funds don’t solve the emergency fund problem directly, but they prevent predictable expenses from draining whatever emergency savings you’ve managed to accumulate.

Setting Up Your First Sinking Funds

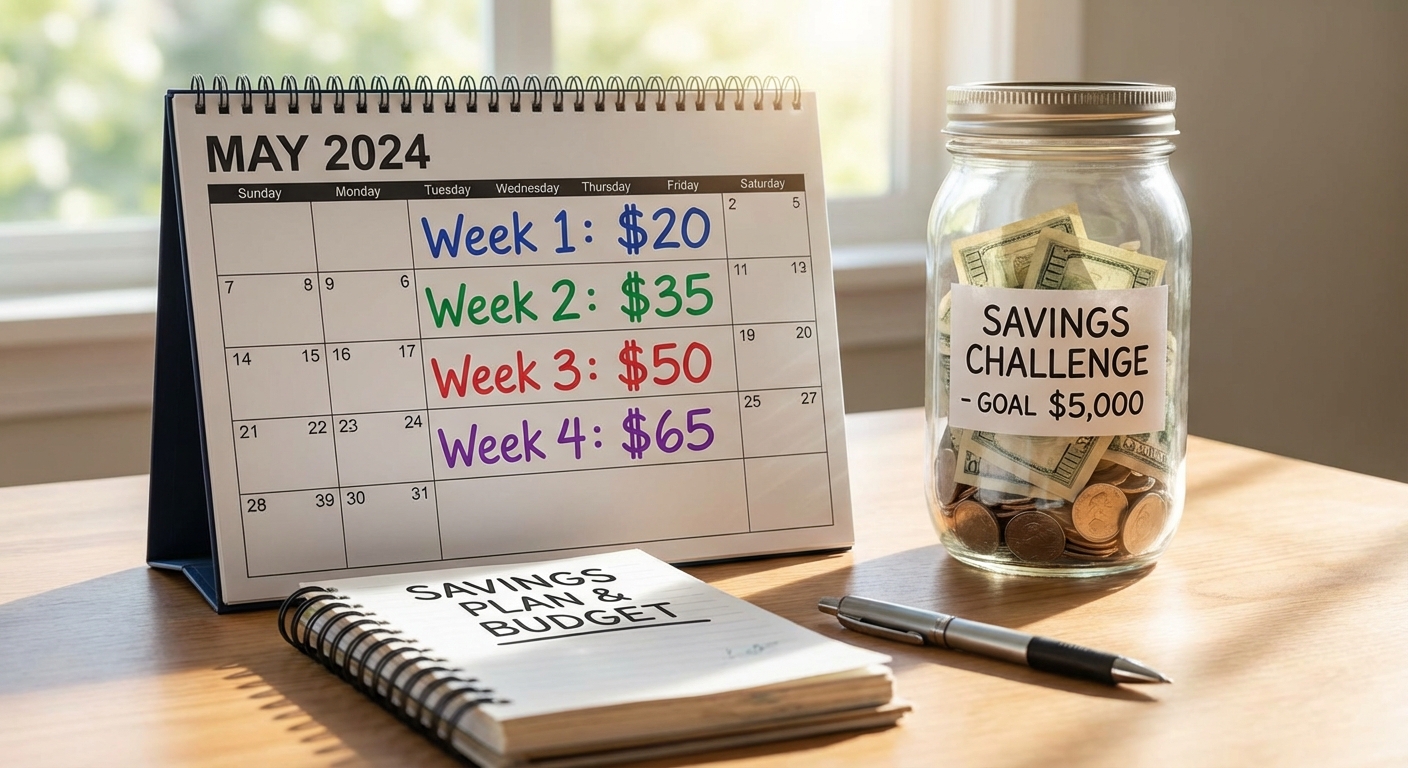

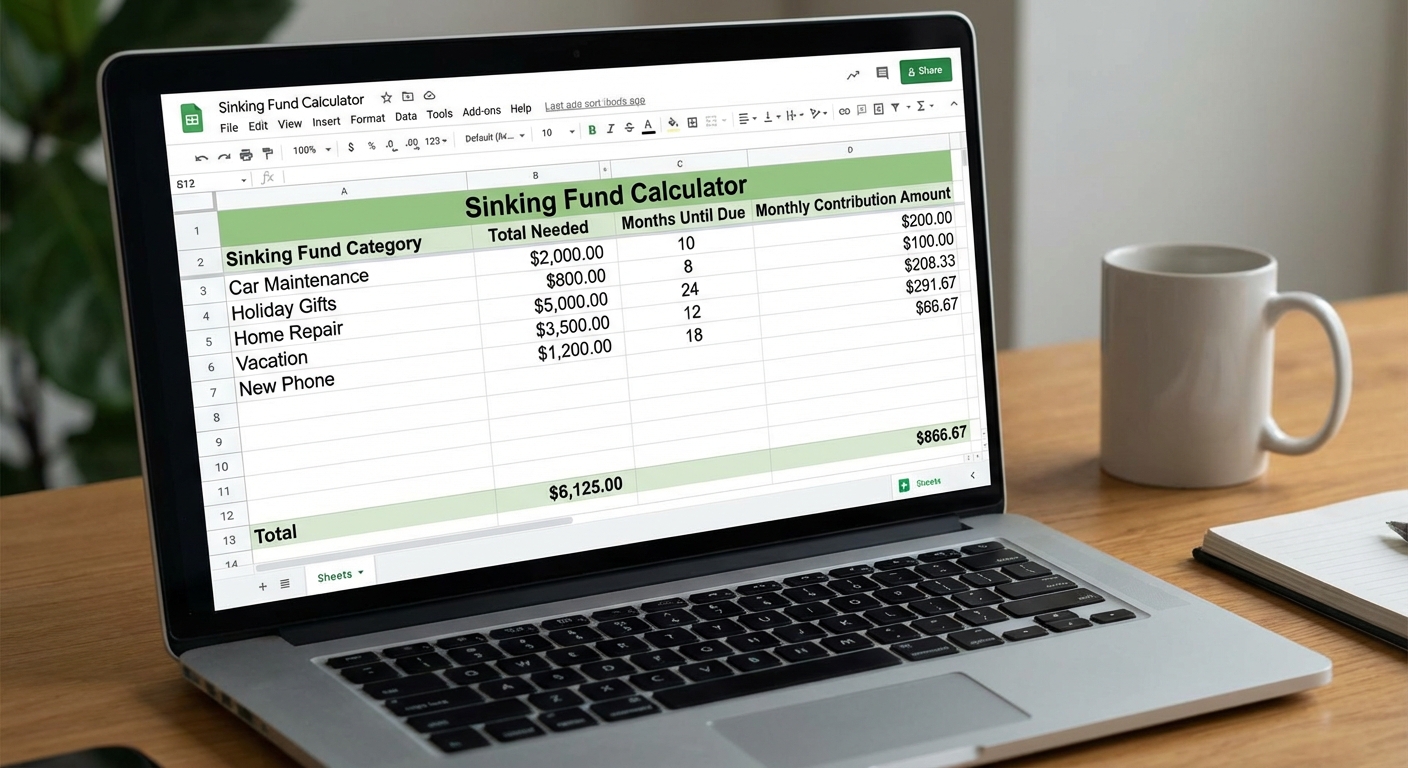

Starting with sinking funds requires two steps: identifying your irregular expenses and calculating monthly contributions.

Step 1: List every non-monthly expense you have. Go through your past year’s bank statements and credit card bills. Look for anything that doesn’t occur every month: insurance premiums, subscription renewals, holiday spending, car maintenance, medical expenses, annual memberships, vacation costs, back-to-school supplies, birthday gifts, home maintenance.

Step 2: Calculate monthly savings needed. For each expense, divide the total cost by the number of months until it’s due. If your car insurance is $900 every six months, that’s $150 per month. If you want to spend $600 on holiday gifts and you have 10 months until December, that’s $60 per month.

Step 3: Decide how to organize the money. You have options here. Some people open separate savings accounts for each sinking fund, using the account nicknames feature most banks offer. Others keep everything in one savings account and track allocations using a spreadsheet or budgeting app. Either approach works; choose based on whether you need the psychological separation of separate accounts.

Step 4: Automate the contributions. Set up automatic transfers from your checking account to your sinking fund(s) on each payday. Automation ensures consistency. You won’t accidentally skip a month or rationalize spending the money elsewhere.

Essential Sinking Fund Categories

While everyone’s expenses differ, certain categories benefit almost everyone.

Car maintenance and repairs: Tires, brakes, oil changes, and unexpected repairs add up. The average car owner spends $1,200-1,500 annually on maintenance and repairs. Saving $100-125 monthly creates a buffer that prevents automotive expenses from becoming financial emergencies.

Insurance premiums: If you pay car, home, or renters insurance annually or semi-annually for the discount, a sinking fund ensures the large payment doesn’t disrupt your monthly budget. Divide the annual premium by 12 and save that amount monthly.

Holiday and gift expenses: December spending catches many people off guard despite happening every single year. Track what you spent last year on gifts, decorations, travel, and entertaining, then divide by 12. Starting in January means each December is financially stress-free.

Medical expenses: Even with insurance, copays, prescriptions, dental work, and vision expenses accumulate. If you have a high-deductible health plan, a sinking fund (or HSA contributions) prevents medical costs from becoming debt.

Home maintenance: Homeowners should budget roughly 1% of their home’s value annually for maintenance and repairs. A $300,000 home means $3,000 per year, or $250 monthly set aside for inevitable repairs and upkeep.

Vacations and travel: Planning a trip is more enjoyable when the money is already saved. Determine your vacation budget, divide by the months until you travel, and contribute automatically. You’ll book the trip knowing it’s already paid for.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Starting too many funds at once. If you try to fund every category immediately, the total monthly contribution might be unmanageable. Start with two or three essential categories, then add more as your budget adjusts.

Forgetting to use the money. Sinking funds only work if you actually spend them on their intended purpose. When car maintenance is due, use the car maintenance fund. When December arrives, spend your holiday fund on gifts. The money exists to be used.

Setting unrealistic contribution amounts. If you can’t consistently make the contributions, the sinking fund fails. Better to save $50 per month reliably than commit to $200 and skip months when money is tight.

Treating sinking funds as optional. Monthly contributions to sinking funds should be treated like bills, not discretionary savings. They’re money you owe your future self for expenses that will definitely occur.

Making Sinking Funds Work Long-Term

The first year of sinking funds requires the most discipline because you’re building balances from zero while expenses may still arrive before funds are ready. Prioritize funds for your nearest predictable expenses. If car insurance is due in three months, that fund takes precedence over vacation savings.

After a full year, sinking funds become self-sustaining. The money flows in monthly and flows out when expenses hit. You stop thinking about irregular expenses as disruptions because they’re simply part of your monthly budget, spread across the year.

High-yield savings accounts make sense for sinking fund money. The funds often sit for months before use, and modern online banks offer 4-5% interest. On $5,000 in combined sinking funds, that’s $200-250 per year in earned interest, essentially free money for money you were saving anyway.

Review your sinking fund categories annually. Expenses change: you might pay off a car and reduce maintenance needs, take up a hobby with new costs, or adjust holiday spending expectations. An annual review ensures your sinking funds match your actual life.

The ultimate goal is eliminating financial surprises. With properly funded sinking accounts, the only expenses that catch you off guard are genuine emergencies, exactly what your emergency fund is designed to handle. Everything else becomes routine, planned, and stress-free.