How do you create a budget that actually sticks? The key is building a simple, flexible system that accounts for your real spending patterns rather than an idealized version of how you think you should spend. Start by tracking what you actually spend for one month without trying to change anything. Then create categories that match your life, build in buffer money for unexpected expenses, and automate as much as possible to reduce willpower requirements.

Most budgets fail for predictable reasons: they’re too detailed to maintain, too restrictive to follow, or too rigid to handle life’s inevitable surprises. The budget that works isn’t the most sophisticated one. It’s the one you’ll actually use week after week. This guide walks through creating a sustainable budgeting system from scratch, whether you’re starting with a blank slate or recovering from past budgeting failures.

Step 1: Track Your Current Spending First

Before creating any budget, you need accurate data about how you currently spend money. Many people skip this step, guessing at their spending patterns, and then create unrealistic budgets destined to fail. Spend one month tracking every dollar without trying to change your behavior. This baseline data will reveal surprises.

Use your bank and credit card statements to capture most spending automatically. For cash purchases, note them in your phone or carry a small notebook. Apps like Mint, YNAB, or Copilot can categorize transactions automatically, though you may need to recategorize some purchases. The goal is a complete picture, not perfect categorization on the first pass.

After a month, review the data and look for patterns. Most people find they spend more than expected on dining out, subscriptions they forgot about, or small daily purchases that add up. This isn’t about judgment. It’s about understanding reality. You cannot build a workable budget without knowing what you’re actually working with. If you’re surprised by how much goes to certain categories, that’s valuable information.

Step 2: Choose Your Budgeting Framework

Several proven frameworks exist for structuring a budget. The right one depends on your personality, financial complexity, and how much time you want to spend managing money. Understanding the options helps you choose a system you’ll stick with.

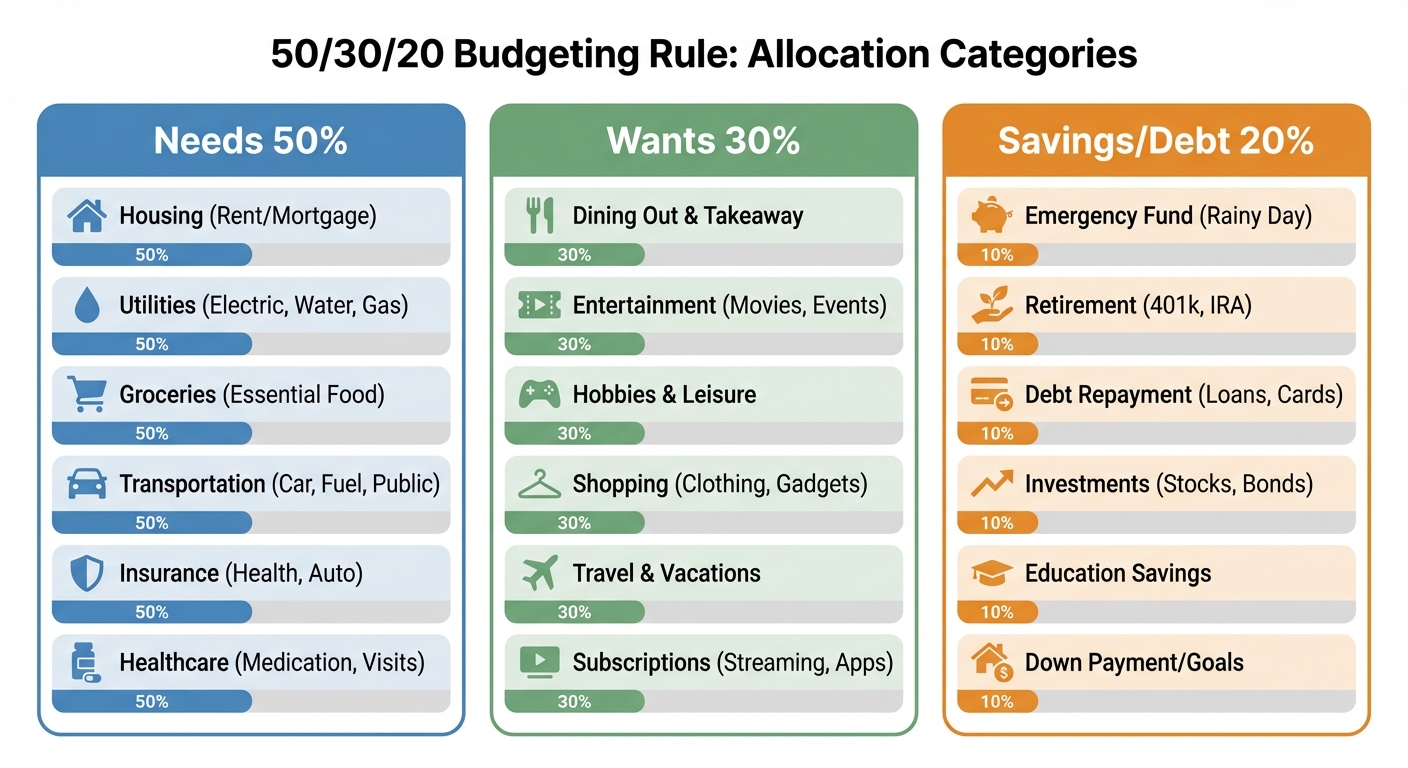

The 50/30/20 rule divides after-tax income into three buckets: 50% for needs (housing, utilities, groceries, minimum debt payments, insurance), 30% for wants (dining out, entertainment, hobbies, subscriptions), and 20% for savings and additional debt payments. This framework works well for people who want simplicity and don’t have complex financial situations. It provides structure without requiring you to track every category individually.

Zero-based budgeting assigns every dollar a job before the month begins. Income minus expenses should equal zero, with “expenses” including savings and debt payments. This method, popularized by apps like YNAB, provides maximum control and awareness but requires more active management. It works well for people who want to optimize their finances or are working toward specific goals like aggressive debt payoff.

The envelope system divides cash into physical envelopes for different spending categories. When an envelope is empty, you’re done spending in that category until next month. This tangible approach works well for people who struggle with abstract numbers on screens and benefit from the psychological impact of watching physical money disappear. Digital versions exist in apps that simulate envelopes with virtual accounts.

For most people starting out, the 50/30/20 rule provides the right balance of structure and simplicity. You can always add complexity later as budgeting becomes habitual.

Step 3: Set Up Your Categories

Based on your tracking data and chosen framework, create budget categories that reflect your actual life. The right categories are specific enough to be meaningful but broad enough that you’re not tracking hundreds of line items. Most people do well with eight to fifteen categories.

Essential categories typically include housing (rent or mortgage, property tax, HOA fees), utilities (electricity, gas, water, internet, phone), groceries, transportation (car payment, insurance, gas, maintenance, or transit passes), insurance (health, renters, life), and minimum debt payments. These are your “needs” in the 50/30/20 framework, the expenses you must pay regardless of what else happens.

Discretionary categories capture your “wants” and might include dining out, entertainment and hobbies, clothing, personal care, subscriptions, and gifts. Keep these categories aligned with how you actually think about spending rather than forcing your life into generic templates. If you’re a foodie who loves trying new restaurants, “dining out” deserves its own category. If you rarely eat out but love buying books, maybe dining out and groceries can merge while “books and media” gets its own line.

Savings categories should include emergency fund contributions, retirement savings beyond any employer match, and specific goal savings like vacation funds, house down payment, or large purchase funds. Treating savings as an “expense” that gets budgeted first, not as whatever is left over, transforms most people’s financial trajectory.

Step 4: Build in Buffer Money

Rigid budgets that account for every dollar break the moment something unexpected happens. And unexpected things happen constantly: a car repair, a medical copay, a friend’s birthday you forgot about, a utility bill that runs higher than usual. Building buffer money into your budget prevents these normal life events from derailing your entire system.

Create a “miscellaneous” or “unexpected” category of 5 to 10 percent of your monthly spending. This isn’t an emergency fund for major crises. It’s cushion money for the routine surprises that don’t fit neatly into other categories. When the car needs an oil change, the dentist visit has a copay, or you need a gift for a last-minute party, this category absorbs the hit.

If buffer money remains at month’s end, roll it forward or redirect it to savings. Some months you’ll use all of it. Others you won’t need any. The point is removing the psychological burden of “failing” your budget every time life doesn’t go according to plan. A budget that acknowledges uncertainty is a budget you can maintain.

For larger irregular expenses, create sinking funds. These are savings buckets for predictable annual or semi-annual expenses like car insurance, holiday gifts, or annual subscriptions. If you pay $1,200 for car insurance annually, budgeting $100 monthly into a car insurance sinking fund means the money is there when the bill comes due. Without sinking funds, these large periodic expenses blow up budgets repeatedly.

Step 5: Automate Everything Possible

The less your budget relies on willpower and memory, the more likely it is to succeed. Automation removes decision fatigue and ensures that the most important financial moves happen without requiring action on your part. The goal is to make good behavior the default.

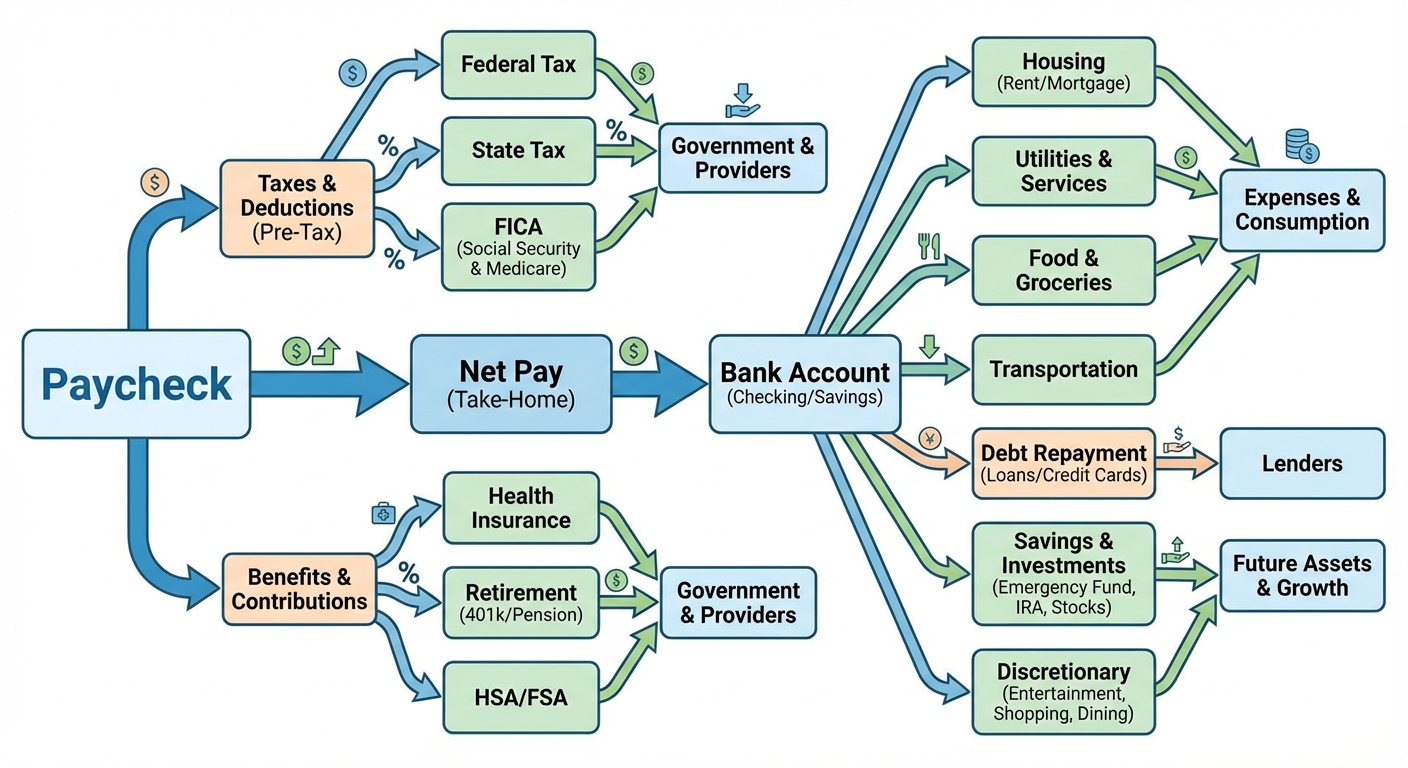

Set up automatic transfers from checking to savings on the day after payday. Many banks allow multiple automatic transfers to different savings buckets. If you’re using the 50/30/20 framework, an automatic transfer of 20% of your paycheck to savings ensures that money never sits in your checking account tempting you to spend it. Pay yourself first, automatically.

Automate all fixed bills: rent or mortgage, utilities, insurance, subscriptions, minimum debt payments. Most providers offer autopay, often with a small discount for setting it up. Review automated payments quarterly to catch services you no longer use, but otherwise let the system run without intervention. Late payments damage credit scores and often incur fees, problems automation eliminates entirely.

For variable spending categories like groceries and dining out, consider using cash or a separate debit card loaded with that month’s allocated amount. When the cash or card balance is depleted, you’re done spending in that category. This creates natural friction and awareness without requiring constant tracking. The research on “mental accounting” shows that physical and practical barriers to spending are more effective than willpower alone.

Step 6: Schedule Regular Check-Ins

A budget isn’t something you create once and forget. It requires periodic review and adjustment. However, the frequency and intensity of these check-ins should match your budget’s complexity and your stage of financial journey. More is not always better.

Weekly check-ins work well when you’re first establishing habits or working intensively on debt payoff. Spend 15 minutes reviewing your spending against your budget. Are you on track in each category? Did any unexpected expenses arise? Adjust your remaining weekly spending accordingly. Many people do this on Sundays to prepare for the week ahead.

Monthly reviews are essential for everyone. At month’s end, compare actual spending to budgeted amounts across all categories. Look for patterns: are you consistently over budget in certain areas? Is your budget realistic, or does it need adjustment? Use this data to refine next month’s budget. The first few months of budgeting often require significant adjustments as you learn what works for your life.

Quarterly deep dives examine broader questions. Are you making progress toward your financial goals? Do your budget categories still reflect your priorities? Has your income or expense structure changed? This is the time to adjust savings rates, reconsider subscriptions, or reallocate discretionary spending based on what actually brings you satisfaction.

If you’ve been trying to maximize your tax refund this year, your budget check-ins are also a good time to ensure you’re tracking deductible expenses properly. Keeping receipts organized throughout the year makes tax time much simpler.

Step 7: Handle Budget Failures Gracefully

Every budget will fail sometimes. The question isn’t whether you’ll go over budget in a category, miss a savings transfer, or have a month where everything falls apart. The question is how you respond. Most budgets are abandoned after a failure because people interpret a single bad month as evidence that budgeting doesn’t work for them.

When you overspend in a category, don’t borrow from savings or skip necessary payments to compensate. Acknowledge the overspending, understand why it happened, and move forward with the next week or month. If overspending was due to a one-time event, no changes are needed. If it reflects an unrealistic budget, adjust the category for next month. Neither case requires guilt or abandonment.

When you have a catastrophic budget month, often due to major unexpected expenses or income disruption, focus on covering essentials and minimum debt payments. Pause savings contributions temporarily if necessary. Once the crisis passes, resume your normal budget without trying to “catch up” on missed savings immediately. Catching up often creates unsustainable pressure that leads to giving up entirely.

Build in planned budget breaks. If you’re working toward intense financial goals, occasional months with relaxed spending parameters prevent burnout. A vacation month or holiday season where you spend more freely, planned in advance and within limits, is different from impulsive budget abandonment. Sustainability requires acknowledging that perfect discipline forever isn’t realistic.

Common Mistakes That Derail Budgets

Understanding why budgets fail helps you avoid those pitfalls. The most common mistakes share a theme: they make budgets harder to follow than necessary, introducing friction that eventually becomes insurmountable.

Too many categories creates tracking burden that few people maintain. If your budget has 40 line items, you’ll probably stop tracking within a month. Consolidate similar spending into broader categories. “Entertainment” can include streaming services, concerts, and movies. “Personal care” can include haircuts, cosmetics, and gym memberships. Fewer categories means less tracking work.

No flexibility built in causes failure at the first unexpected expense. Life includes unpredictable costs. Budgets that don’t acknowledge this are fantasies, not plans. Buffer money and sinking funds transform unpredictable expenses into routine budget line items.

All or nothing thinking destroys budgets after minor failures. One expensive dinner doesn’t mean the budget is ruined and you should give up for the month. One missed savings transfer doesn’t mean the whole system is broken. Budgeting is about overall patterns, not perfection in every transaction.

Budgeting based on ideal behavior rather than real patterns creates budgets that were never realistic. If you’ve spent $600 monthly on dining out for the past year, budgeting $200 sets you up for failure. Either budget closer to your actual spending or make deliberate, incremental changes over time. A budget that reduces dining out to $500 this month, then $400 next quarter, is more likely to succeed than an immediate drastic cut.

Key Takeaways

Creating a budget that sticks requires starting with real spending data rather than wishful thinking. Track your spending for at least one month before creating categories. Choose a simple framework like 50/30/20 that provides structure without overwhelming detail. Build buffer money into every budget to handle life’s inevitable surprises gracefully.

Automate savings and fixed expenses to remove willpower from the equation. Schedule regular check-ins, weekly when starting out, monthly always, and quarterly for deeper review. When budget failures happen, respond with adjustment rather than abandonment. The goal is a sustainable system that improves your finances over time, not a perfect month that you can never repeat.

Start simple. A basic budget you follow is infinitely more valuable than a sophisticated budget you abandon. You can add complexity as budgeting becomes habitual. The best time to start is now, with whatever income and expenses you currently have. Every month of intentional financial management compounds into significant long-term change.