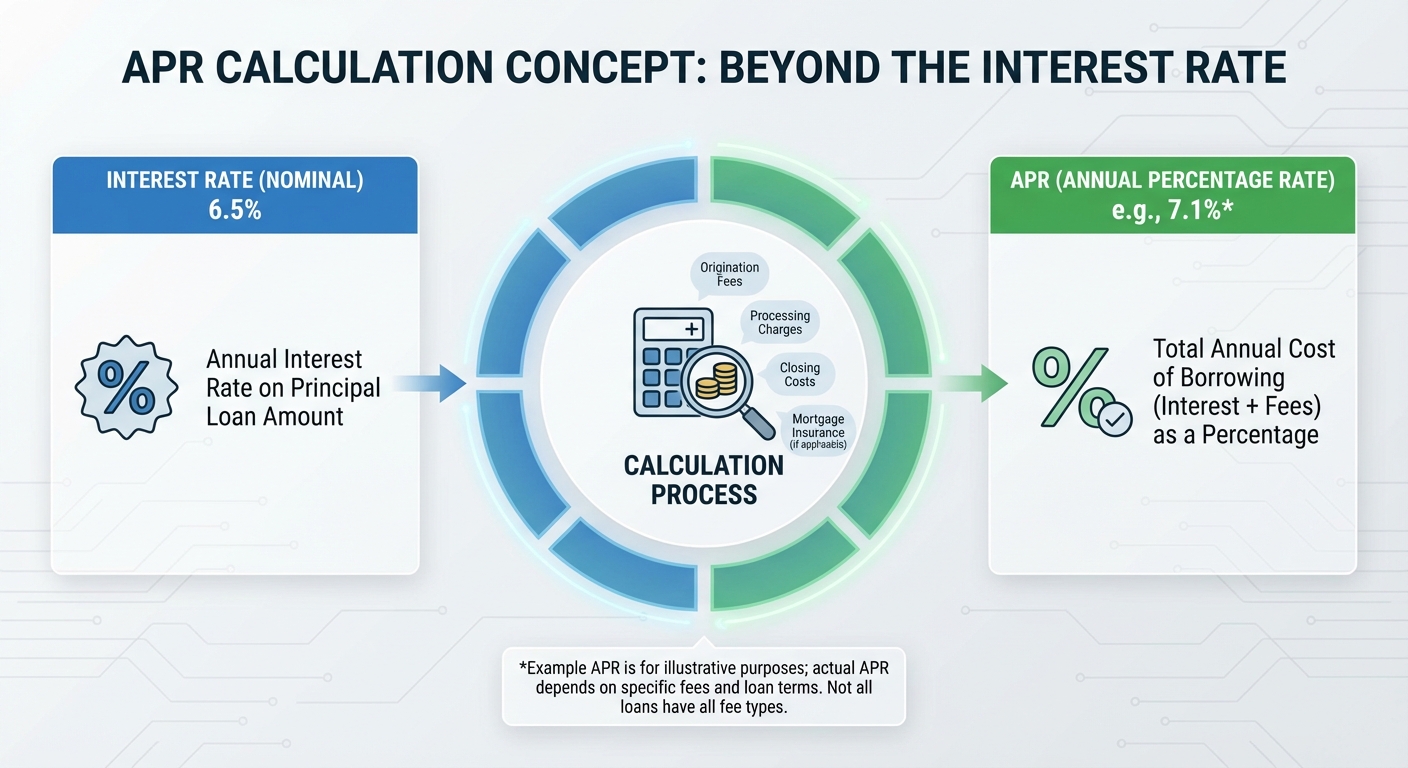

What’s the difference between APR and interest rate? The interest rate is the base cost of borrowing money, expressed as a percentage. APR (Annual Percentage Rate) includes the interest rate plus additional fees and costs, giving you a more complete picture of what a loan actually costs. For mortgages, the APR will always be higher than the interest rate because it folds in origination fees, points, and other closing costs. For credit cards, APR and interest rate are essentially the same thing.

When comparing loans, APR is almost always the better number to use because it accounts for costs that interest rate alone hides. Two mortgages with identical interest rates can have very different APRs if one has higher fees. The lender offering “no closing costs” might actually be charging a higher rate to compensate, which the APR will reveal. Understanding this distinction helps you spot deals that look better than they are and find loans that genuinely cost less.

How Interest Rate Works

The interest rate represents the pure cost of borrowing money before any fees enter the picture. If you borrow $100,000 at a 7% interest rate, you’ll pay $7,000 in interest over the first year (assuming simple interest, though most loans use compound interest which is slightly more complex).

Lenders set interest rates based on several factors. The baseline is driven by broader economic conditions, particularly the Federal Reserve’s benchmark rate. Your credit score, loan amount, down payment, and loan term all influence where your rate falls relative to that baseline. A borrower with excellent credit might qualify for rates a full percentage point or more below someone with fair credit.

Interest rates are straightforward to understand because they measure one thing: the percentage you pay to borrow the principal. This simplicity is also their limitation. A loan with a 6.5% interest rate sounds cheaper than one at 6.75%, but if the lower-rate loan has $8,000 in fees compared to $2,000 for the higher-rate loan, the actual cost picture is more complicated. That’s where APR becomes useful.

How APR Captures the Full Cost

APR takes the interest rate and adds mandatory fees, then recalculates what the effective rate would be if those fees were spread across the loan term. The result is a single number that accounts for both the cost of borrowing and the cost of obtaining the loan.

For mortgages, APR typically includes origination fees (often 0.5% to 1% of the loan), discount points if you pay them, mortgage broker fees, certain closing costs, and private mortgage insurance if applicable. It doesn’t include title insurance, appraisal fees, or some other closing costs, so even APR doesn’t capture every expense, but it captures enough to make meaningful comparisons.

Here’s a concrete example. Consider two 30-year mortgages for $300,000. Loan A has a 6.5% interest rate with $9,000 in fees. Loan B has a 6.75% interest rate with $3,000 in fees. Loan A’s APR might be 6.75% once fees are factored in, while Loan B’s APR might be 6.85%. Despite Loan A having a lower interest rate, the higher fees make its true cost only slightly better than Loan B. If you planned to refinance or sell within five years, Loan B might actually save you money because you’d have less time to recoup those upfront fees through the lower rate.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau requires lenders to disclose APR on mortgages specifically because comparing interest rates alone can be misleading. This disclosure requirement gives borrowers a standardized way to compare offers from different lenders.

Why APR Matters Most for Mortgages

Mortgages are where the APR versus interest rate distinction matters most, because mortgage fees can run into thousands or tens of thousands of dollars. A $400,000 mortgage might have $10,000 to $15,000 in combined fees and closing costs, enough to significantly impact the true cost of borrowing.

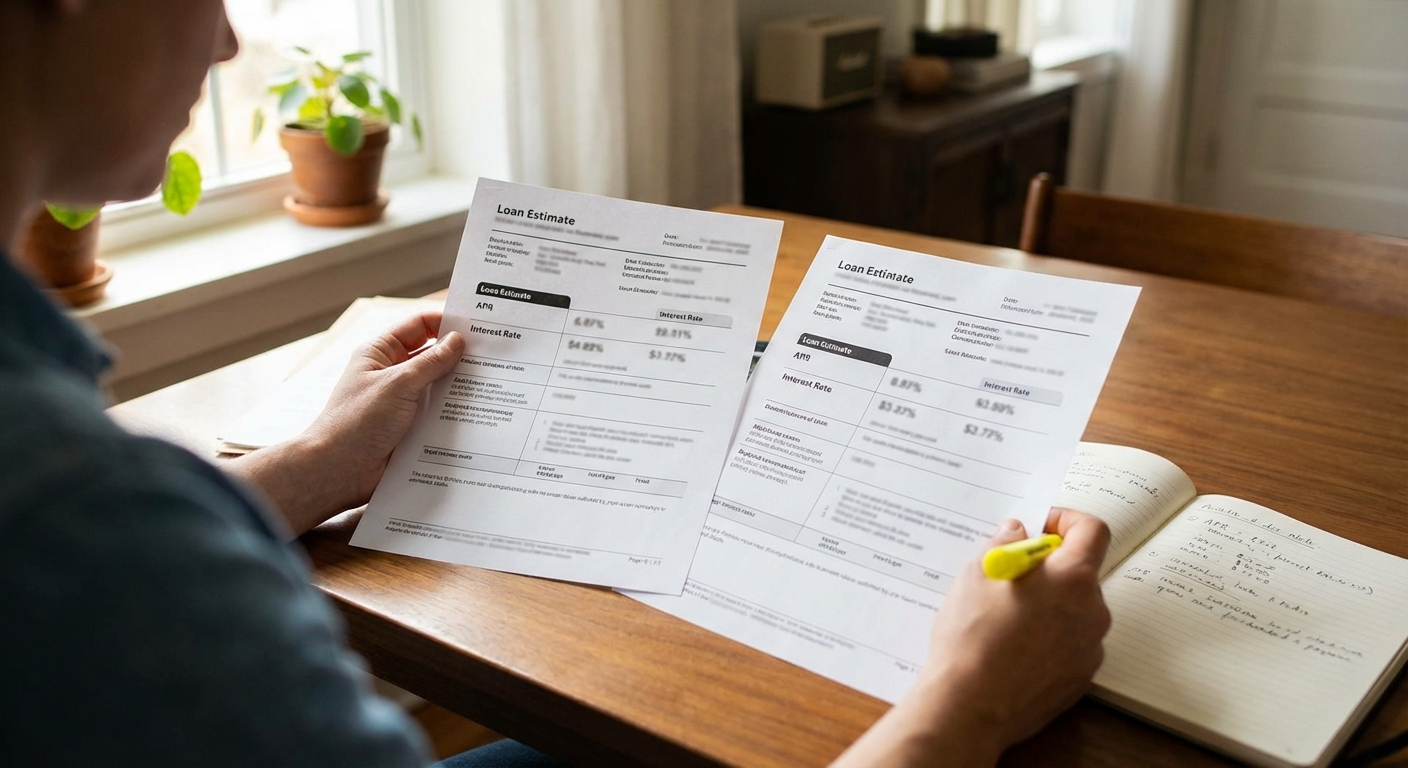

When shopping for a mortgage, request the Loan Estimate form from each lender you’re considering. This standardized document, required by federal law, shows both the interest rate and APR prominently, along with itemized fees. Comparing Loan Estimates side-by-side gives you a clear picture of which lender offers the best deal overall.

The interest rate still matters for calculating your monthly payment. Your principal and interest payment is based on the interest rate, not the APR. A $300,000 loan at 6.5% has a monthly payment of about $1,896, regardless of fees. But over the life of the loan, or however long you keep it before selling or refinancing, the APR tells you what you’re really paying.

Credit Cards: APR and Interest Rate Are the Same

For credit cards, the situation is simpler. Credit card APR and interest rate are effectively identical because credit cards don’t have the upfront fees that make mortgage APR higher than the interest rate. When a credit card advertises a 22% APR, that’s also the interest rate.

What makes credit cards tricky is how interest is calculated. The APR is an annual figure, but credit card interest compounds daily. Your card issuer divides the APR by 365 to get a daily periodic rate, then applies that rate to your balance each day. A 22% APR becomes a daily rate of about 0.0603%, which compounds over the month.

If you carry a balance, understanding the APR helps you calculate the cost. A $5,000 balance at 22% APR would accrue roughly $91 in interest over a month if unpaid (the exact amount varies based on daily balance fluctuations). Paying off your full statement balance each month means you pay no interest at all, making the APR irrelevant for people who never carry a balance.

Credit cards often have multiple APRs: one for purchases, one for cash advances (usually higher), and one for balance transfers. The introductory 0% APR offers on new cards are temporary, typically lasting 12 to 21 months before jumping to the regular rate. When comparing credit cards, look at both the introductory offer and the ongoing APR you’ll face afterward.

When Interest Rate Matters More Than APR

While APR is generally the better comparison tool, there are situations where the interest rate deserves more attention.

For adjustable-rate mortgages, the interest rate is what changes over time, not the APR. Your APR is calculated based on initial conditions, but if rates rise after your fixed period ends, your actual payments will increase based on the new interest rate. Understanding the rate caps and adjustment intervals matters more than the initial APR.

If you plan to stay in your home for a very short time, a loan with a higher APR but lower upfront fees might cost less total. The lower fees save you money immediately, while the higher rate has less time to accumulate. Conversely, staying for the full 30-year term favors lower interest rates even if APR is higher due to fees.

For lines of credit like HELOCs, fees are typically minimal, so interest rate and APR are usually close. The variable nature of these products means the rate will change over time anyway, making the initial APR less meaningful for long-term planning.

How to Use Both Numbers When Comparing Loans

The smartest approach uses both numbers strategically. Start with APR to identify which offers are genuinely competitive, then look at interest rate and fees separately to understand why.

Calculate your break-even point for loans with different fee structures. If Loan A saves you $100 per month compared to Loan B but costs $6,000 more in fees, you need to keep the loan for at least 60 months (5 years) before the lower payment makes up for the higher fees. If you expect to move or refinance sooner, the higher-fee loan might actually cost you more.

For budgeting purposes, your monthly payment is based on interest rate, so that number determines what you need to afford each month. For comparing total loan cost, APR gives you the fuller picture. Use both numbers, but for different purposes.

Key Takeaways

Interest rate is the base cost of borrowing, expressed as a percentage of the loan amount. APR adds mandatory fees to that rate, showing a more complete cost picture. For mortgages, APR is almost always higher than interest rate because of origination fees, points, and other closing costs. For credit cards, APR and interest rate are the same since credit cards don’t have those upfront costs.

When comparing mortgage offers, APR is the better comparison tool because it accounts for hidden costs that interest rate alone doesn’t show. However, your monthly payment is calculated from the interest rate, not APR. Understanding both numbers, and when each matters most, helps you make smarter borrowing decisions.

If you’re working on improving your overall financial picture, understanding loan costs pairs well with maximizing your tax refund and building a budget that actually sticks. Together, these fundamentals give you control over both sides of your financial equation.