What happens if you don’t file your taxes? If you owe money, the IRS charges a failure-to-file penalty of 5% of your unpaid taxes for each month you’re late, up to a maximum of 25%. You’ll also face a separate failure-to-pay penalty of 0.5% per month, plus interest on any balance due. If you’re owed a refund, there’s no penalty for filing late, but you only have three years to claim it before you lose that money permanently.

The distinction between not filing and not paying matters significantly. The failure-to-file penalty is ten times larger than the failure-to-pay penalty, which means you should file your return even if you can’t pay what you owe. The IRS offers payment plans for people who owe but can’t pay immediately, and working within their system is always better than avoiding the situation entirely.

The Penalties for Filing Late

The IRS treats failure to file as a more serious offense than failure to pay, and the penalties reflect this distinction. Understanding how these penalties accumulate helps explain why filing, even without payment, is always the better choice.

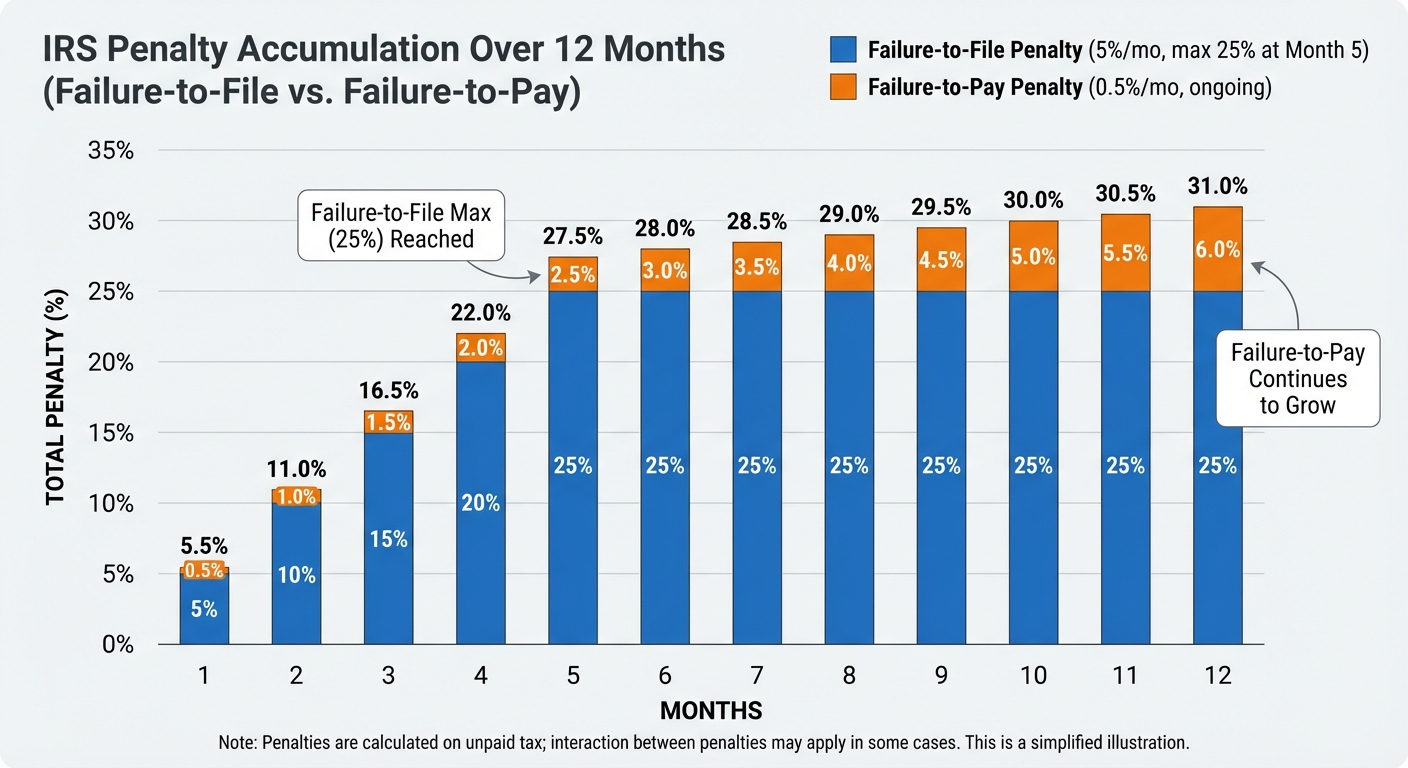

The failure-to-file penalty starts at 5% of your unpaid tax bill for each month or partial month your return is late, capping at 25% of the total. If you’re 5 months late on a $5,000 tax bill, the penalty alone adds $1,250 to what you owe. This penalty applies to the tax due after subtracting any withholding and estimated payments you’ve already made.

The failure-to-pay penalty is gentler at 0.5% per month of your unpaid taxes, also capping at 25%. On that same $5,000 debt, the first month’s penalty is just $25. The IRS also charges interest on your unpaid balance, currently around 8% annually, compounded daily. This interest applies to both the original tax debt and any accumulated penalties.

When both penalties apply in the same month, the failure-to-file penalty is reduced by the failure-to-pay amount, effectively making the combined penalty 5% for months when both apply. After the first 5 months, only the failure-to-pay penalty continues accumulating. The practical result is that your tax debt can grow substantially if you ignore it, but the worst damage happens in those first few months of non-filing.

When You’re Owed a Refund

The situation changes completely if the IRS owes you money. There’s no penalty for filing a late return when you’re due a refund because the penalty is calculated as a percentage of unpaid taxes, and you don’t have any. The IRS isn’t going to charge you for being slow to collect money they owe you.

However, you do face a deadline to claim your refund. You have three years from the original due date to file your return and receive your refund. After that window closes, the money becomes the property of the U.S. Treasury, and you cannot claim it. The IRS estimates that over $1 billion in refunds goes unclaimed every year because people don’t file returns they didn’t realize they needed to file or simply let too much time pass.

This three-year rule catches many people who had taxes withheld from paychecks but earned too little to actually owe taxes. Students, part-time workers, and people who experienced job loss often have refunds waiting that they never claimed. If you think you might have unfiled returns from recent years, it’s worth checking whether you’re leaving money on the table.

Even if you’re beyond the three-year window, filing old returns can still be worthwhile. It stops the statute of limitations clock for IRS audits, documents your income history for Social Security benefits, and may be required for loan applications or other financial processes.

What the IRS Actually Does to Collect

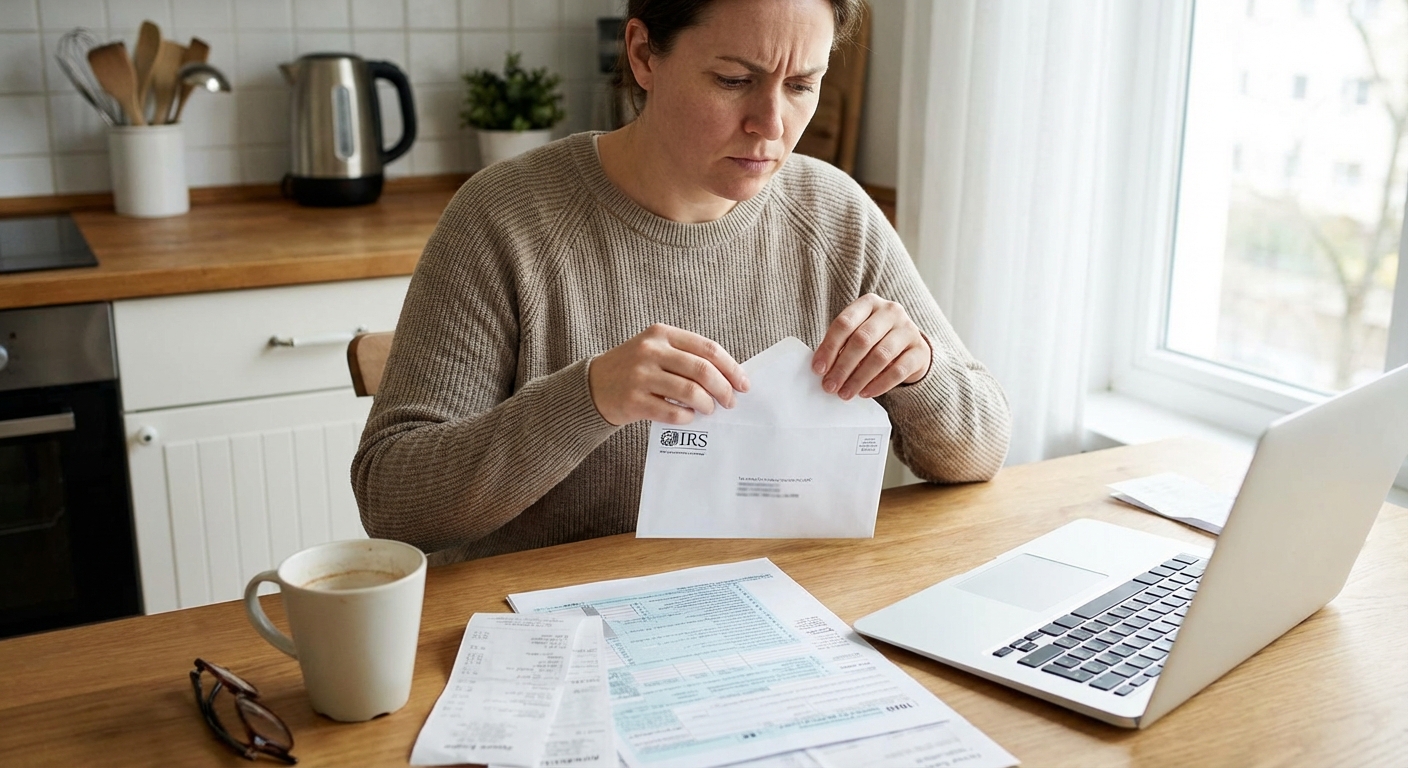

The IRS follows a predictable escalation pattern when pursuing unfiled returns and unpaid taxes. Understanding this process helps clarify what to expect and why acting sooner is always better than waiting.

Initially, the IRS sends a series of notices. The first is typically a CP14, informing you of a balance due. If you don’t respond, you’ll receive increasingly urgent letters over the following months. These notices explain your balance, including penalties and interest, and provide instructions for payment or disputing the amount.

If notices go unanswered for several months, the IRS may file a substitute return on your behalf. They use information from W-2s, 1099s, and other documents they’ve received to calculate what you owe. These substitute returns don’t include deductions or credits you might be entitled to, so they almost always show a higher tax liability than if you’d filed yourself.

For significant debts that remain unpaid after repeated notices, the IRS can take enforced collection action. This includes levying bank accounts (seizing money directly), garnishing wages, placing liens on property, and in extreme cases, seizing assets. However, these actions require substantial notice and typically only occur after years of non-response. The IRS would much rather you set up a payment plan than go through the expense of enforced collection.

How to Fix Unfiled Tax Returns

If you have unfiled returns, the best time to address them was years ago. The second-best time is now. The IRS has programs designed to help people catch up, and voluntary compliance before the IRS contacts you typically results in better outcomes.

Start by gathering your records for each unfiled year. If you don’t have your documents, you can request a Wage and Income Transcript from the IRS, which shows all income reported to them under your Social Security number. This includes W-2s, 1099s, and other information returns. You can request these transcripts online at irs.gov, by phone, or by mail.

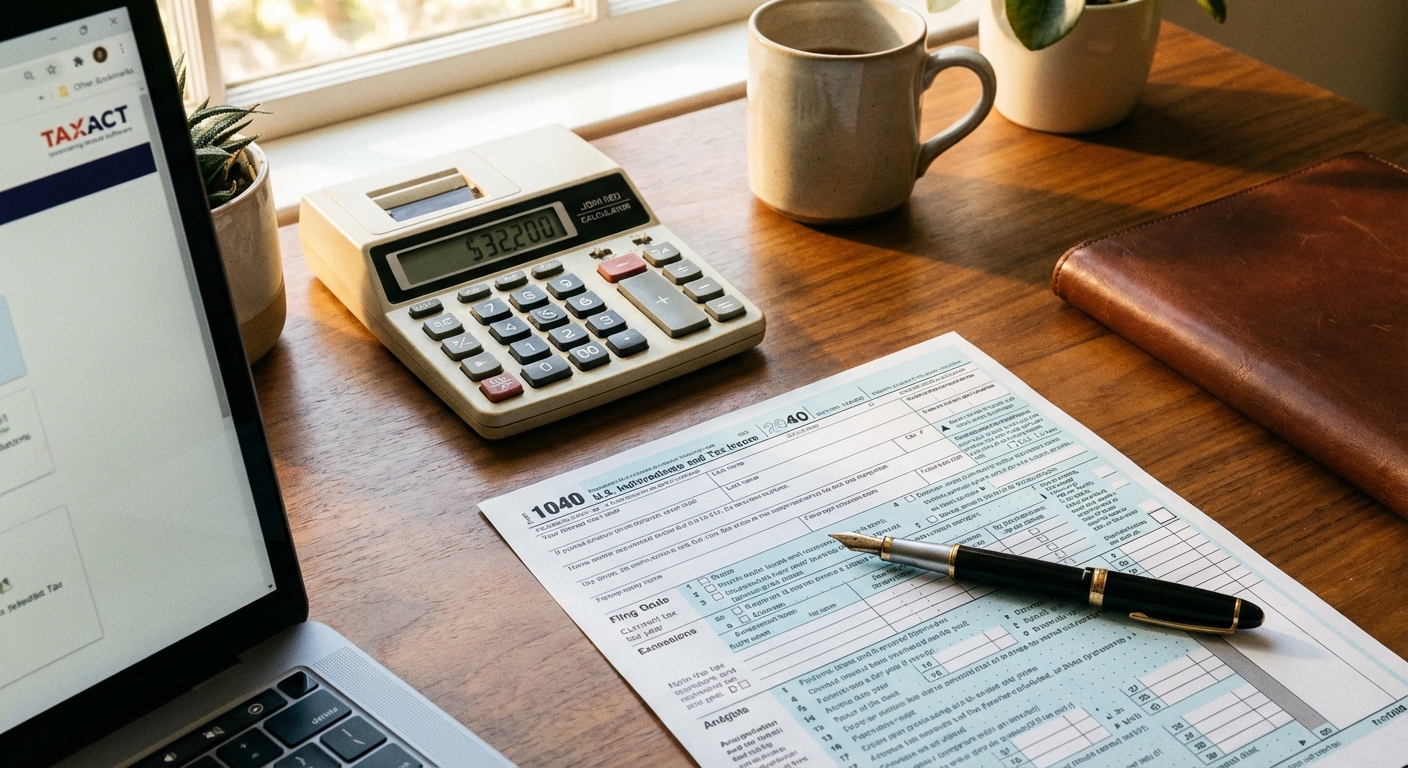

File your returns using the forms from the applicable tax year, not the current year’s forms. Tax laws change annually, and you need to use the version that was in effect for each year you’re filing. The IRS website archives old forms and instructions. Consider using tax software or a professional for complex situations, as errors on late returns can create additional problems.

When you file, include whatever payment you can afford. If you can’t pay the full amount, the IRS offers several options. An Installment Agreement lets you pay monthly over up to 72 months. For debts under $50,000, you can set this up online without speaking to anyone. Offer in Compromise programs may reduce your total debt if you can prove financial hardship, though acceptance is relatively rare.

Special Circumstances and Exceptions

Certain situations modify the standard rules. Taxpayers living abroad have automatic extensions and different filing requirements. Members of the military in combat zones receive extended deadlines that can push filing requirements back years. Victims of federally declared disasters may receive deadline extensions for their affected regions.

The IRS can also waive penalties for “reasonable cause,” though they define this narrowly. Death of an immediate family member, serious illness, natural disasters, and reliance on incorrect professional advice can qualify. “I forgot” or “I was too busy” do not qualify. You must request penalty abatement in writing, explaining your circumstances and providing documentation.

Criminal prosecution for tax evasion is possible but rare, reserved for cases involving fraud or deliberate concealment of income. Simply being disorganized or overwhelmed isn’t a crime. The IRS distinguishes between civil penalties, which are financial, and criminal prosecution, which requires proving intent to defraud. The vast majority of unfiled return cases are handled entirely through civil processes.

Key Takeaways

Not filing your taxes triggers penalties of 5% per month on any tax owed, up to 25%. The failure-to-pay penalty is smaller at 0.5% per month, which means you should always file your return even if you can’t pay. Interest also accrues on unpaid balances. If you’re owed a refund, there’s no penalty for late filing, but you have only three years to claim it.

The IRS follows a predictable escalation from notices to enforced collection, but they prefer working out payment arrangements. If you have unfiled returns, request your Wage and Income Transcripts, file the missing returns, and set up a payment plan if needed. Taking action, even years later, is always better than continued avoidance.

For those preparing for the current tax season, understanding how to maximize your refund starts with actually filing. If you’re self-employed, don’t forget about the home office deduction as one of many strategies to reduce your tax burden legally.